As to the Spanish stock of our Southwest, it is certain to me that we do not begin to appreciate the splendor and sterling value of its race element. Who knows but that element, like the course of some subterranean river, dripping invisibly for a hundred or two years, is now to emerge in broadest flow and permanent action?

Walt Whitman

Spanish Origins 1600s

It is well documented that the first horsemen to arrive in the American South and Southwest were of Spanish origin. They migrated from Mexico up into New Spain which would have consisted largely of what we now know as California, New Mexico, Texas, Arizona and perhaps even up into Nevada and Utah. The Franciscan missions were centers of commerce for, among other things, the tallow and hide industries and the country had grass expanses that were perfectly suited for raising cattle. Spanish cattlemen were accustomed to using horses to tend their herds and used the long garocha (lance) to prod and move their herds.

Evolution and Development

The art of horsemanship brought to New Spain was derived from the Doma Vaquera, the traditional Spanish school of dressage which in turn developed from the Moorish invasion of Spain during the 8th century. The Moors defeated the Spanish using their highly refined horsemanship and ability to utilize smaller more versatile and manoeuvrable Barb horses. The African Barb stock were later refined by the Spanish and the Portuguese into what we now recognize as the Andalusians and Lusitanos. These were among the earliest horses shipped to the Americas and along with the Thoroughbred form the root stock for the development of now popular American Quarter Horse.

Horsemanship itself developed and evolved in the New World with wide open plains and no fences time was no longer of the essence, there was always manana (tomorrow). The Vaqueros replaced their cumbersome garocha poles with more manageable riata (lasso or lariat) usually made from rawhide braided into a rope. Rawhide was used extensively as it was a readily available material that could be braided to serve many purposes from the riata to the bosal (noseband) and even into some forms or parts of clothing. More consideration was given to the development of horses over time rather than trying to get them ready in a hurry and many Vaquero would have a string of several horses at various stages of development and each used for a different purpose.

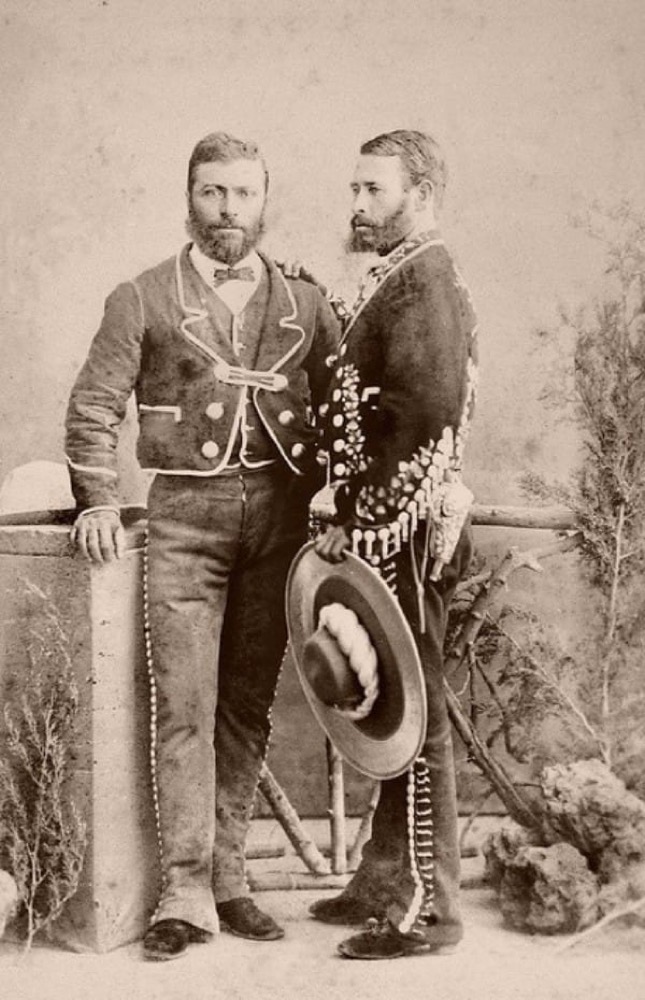

By the early to mid 1800s Northern European influences began to be felt as the Spanish colonies were driven out of the western states and the mission system replaced largely with British business interests. There was an intermingling of styles in terms of culture, horses and horsemanship. The demand of the cattle industry changed from tallow and hides to beef. The livestock industry expanded and became the main source of income for many settlers and the horsemanship culture continued to develop to suit the needs of the day. Spanish words were Anglicized and the Vaquero became the Buckaroo, the Mecate became the McCarty while Jaquima changed to Hackamore and so on.

Gradually the style of horsemanship itself changed becoming regionalised and while some regions maintained the slow pace, always looking towards manana, others, most notably Texas, became more hurried. As noted by Buster McLaury when he said his father would tell him, “hurry every time you think about it and keep it on your mind”. Buster is a Texan who started life as a cowpuncher but later became a Buckaroo and continues to teach a much more refined style of horsemanship at clinics and ranches.

Twentieth Century Cowboys

Between the late 1800s and the present time horses were gradually replaced by mechanisation and automated feedlots replaced the open range. The Vaquero cowboy slowly fell into the history books of America with fewer and fewer ranches continuing to maintain the old traditions. The traditional Vaquero style of horsemanship was mostly kept alive on the dwindling ranches of the Great Basin (Wyoming, Idaho, Utah, Nevada, Oregon, California). It might well have fallen further into obscurity were it not for the efforts of such notables as Tom and Bill Dorrance and the protégés such as Ray Hunt and Martin Black as well, of course, as Buck Brannaman who popularized the tradition through the movie “The Horse Whisperer” and his own documentary film “Buck”.

After years of working to find ways to control and dominate horses many equestrians are realizing that are better ways of developing communication with them. Pioneers such as Sheila Varian demonstrated the efficacy of the Vaquero traditions to the world of dressage and today other schools are slowly following suit. The emergence of so called “natural horsemanship” has helped rejuvenate interest in the art of the Vaquero and we are slowly seeing more riders awakening to the possibilities of becoming horsemen through this time honoured tradition.